Book Review by Bud Gundy

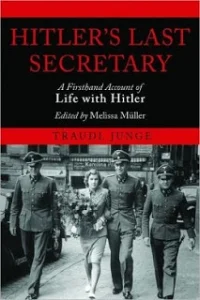

When I start reading about a topic, I often find myself obsessed for a while. So right after I finished The Third Reich at War (review below) I decided to read a book I’ve been meaning to get to for years. Hitler’s Last Secretary by Traudl Junge is an engrossing read, every bit as mesmerizing as the movie it inspired, “Downfall.”

Traudl Junge is the secretary in question, and the forward gives us a good overview of the scope of her life and how she came to see Hitler for what he really was, looking back on her gullibility with amazement.

But her own memoirs offer very little in the way of that insight, and I recommend you watch the documentary interview conducted shortly before she died for that sort of perspective. These memoirs were written in 1947, while the memories were still fresh in her mind, and she hadn’t yet grasped the true nature of the story she relays with such a dispassionate (dare I say Germanic?) voice.

She begins her story with her life in Munich as a girl, before her parents ended their unhappy marriage. While she didn’t hate her father, he was an absent parent – working in Turkey for several years before the divorce. She has evident admiration for her mother, a single woman struggling to raise her children and to give them a decent upbringing with the help of her own parents. Even still, both parents are shadowy enigmas, making it easy, I suppose, to identify her later devotion to Hitler as the love for a misbegotten father figure.

Junge tells breezily clueless stories from her school years, remarking on the disappearance of Jewish friends with a voice struggling with nothing greater than confusion. She never joined the Nazi party, partly because of her mother’s warnings to remain aloof from the savage political forces at work in Germany, and partly because her outlook was decidedly apolitical. One is tempted to feel scorn for a girl so willfully ignorant of the terror for anyone identified as an outsider in Germany. In the documentary, she stated that she found it hard to forgive herself for this, and I have to say that I agree.

She followed her older sister to Berlin to start a career as a dancer, but by this time the war was in full swing, and Germany was not clamoring for new dancers. She secured a secretarial job before a family friend tipped her off to an open position at the Reich Chancellery. After working there a short while, she found herself among a group of just nine women who are asked to submit to a battery of tests to join the small circle of women who work exclusively as secretaries to Hitler.

Junge is frank about Hitler’s kindness and consideration, his doting affection for his secretaries and others who served him in crucial but low-level positions. But he is a demanding boss, too, expecting his personal workers to be available at any time, and to conform to his vampire-like schedule of staying up all night and sleeping until early afternoon.

At first, she is excited by the thrill of living at the center of power, with all the famous names sweeping in and out – Speer, Borman, Goring, Goebbels, Himmler, Mussolini and other notorious people. Details of this life are rich and fascinating – the tedium of listening to Hitler’s famously dull nightly lectures, the glamour provided by Evan Braun, the distinction of living and working in Hitler’s various enclaves. We see the regular entourage at dinner, at work, at play. It is a fascinating glimpse into this world, especially since so much of it seems routine and, at times, utterly banal.

As the war progresses, Junge writes of the hope and inspiration that Hitler gave those in his immediate circle. She does not write of the sense of doom that many in Germany felt, starting in 1941, when they realized that Hitler had expanded the war too quickly, and that that country was rushing headlong to defeat. She lived in a gilded bubble, something she did not realize until many years later.

Junge marries one of Hitler’s valets, but she is emotionally vacant about this episode. Her husband is transferred to the Western front where he is eventually killed.

The final year is easily the most engrossing. Hitler survives the assassination attempt at his Wolf’s Lair headquarters but never really recovers. His health deteriorates, a physical manifestation of his intellectual realization that everything is falling apart. Naturally, he blames everyone else for his own failures. Finally, his inner circle moves into the bunker beneath the Reich Chancellery to wait for the arrival of the Russian army and for Hitler’s demise.

He announces that he’s decided to kill himself, and along with a handful of other stalwart supporters, Junge refuses leave the bunker when a final chance presented itself. She says she surprised herself with this decision, but it allowed her to see Hitler’s final days with a very unique insider’s perspective. This is a riveting read.

Amazingly, Junge only felt a single instance of anger toward Hitler before his suicide. It wasn’t until he was dead that a more permanent sense of fury settled into her feelings about him. Only then did she wonder why he had prolonged the war, and thus the suffering.

As usual, people mistook vanity for courage, hubris for resolve, pettiness for ideological consistency, and Junge was only one of the millions who did so in Germany at that time (let’s not get into the scary recent parallels in our own country). I believe she was being honest when she says that she foolishly believed Nazi propaganda about the war being a defensive move for Germany. I’m happy that she eventually realized that this was no excuse.

I’ve heard criticism of the various incarnations of her story for granting Hitler the ability to show kindness and solicitude, but as much as a I sympathize with those critics I have to disagree. I think it’s a mistake to make cartoon characters of human monsters. Pretending that hateful people are hateful in every respect only makes it more difficult to identify true evil. A dull and ridiculous little man can inspire needless war and genocide. Shouldn’t we know that and be on guard?

Available online here